A Shift in Perspective: Compassionate Approaches to Voyeuristic Disorder

A Shift in Perspective: Compassionate Approaches to Voyeuristic Disorder

The layers of Voyeuristic Disorder are a complex interplay of psychology, relationships, and identity. Dive into the evolution of our understanding, from punitive measures to compassionate interventions, and explore the profound implications on personal connections and self-worth.

Voyeuristic Disorder, detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5-TR), is a specific type of paraphilic Disorder characterized by recurrent and intense sexual arousal from observing an unsuspecting person who is naked, in the process of undressing, or engaging in sexual activities (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2023). This arousal is typically experienced through fantasies, urges, or voyeuristic behaviors.

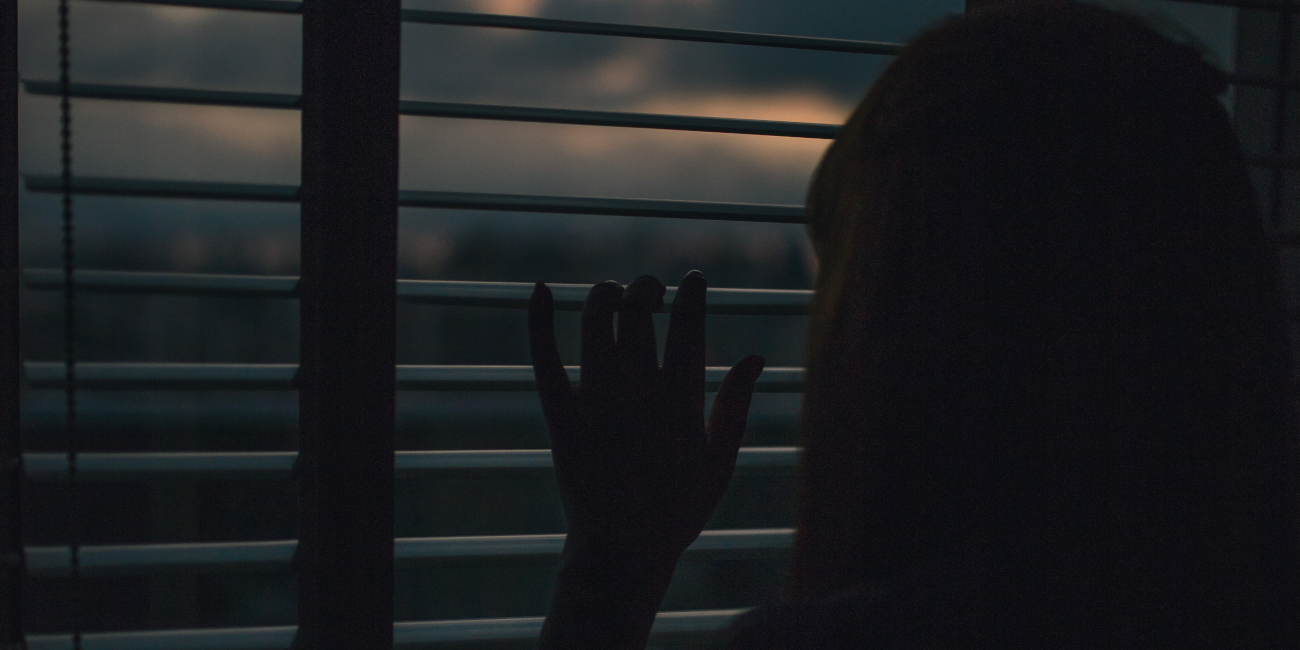

Individuals with Voyeuristic Disorder go beyond the occasional and perhaps "normal" curiosity about others. Their behavior often involves seeking out situations where they can covertly observe others, commonly strangers, in private or intimate settings without the observed person's knowledge or consent. This could involve, for instance, peeping into someone's window or using hidden cameras. In many cases, watching is the primary source of the person's arousal rather than what is being observed.

The urge to observe others is not an occasional or fleeting desire for these individuals. Instead, it becomes a predominant and compelling aspect of their sexual lives. Many recognize the illicit and invasive nature of their behavior. This recognition can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, or distress. However, the compulsion to engage in voyeuristic behaviors often supersedes these feelings, making it challenging for them to resist or stop their actions (Kafka, 2010).

It is crucial to differentiate between individuals who occasionally engage in voyeuristic behaviors, such as watching explicit videos or movies with intimate scenes, and those with the Disorder. To be diagnosed with Voyeuristic Disorder, the person's behavior must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Additionally, the DSM-5-TR stipulates that the individual must be at least 18 years of age and have had recurrent urges or fantasies for at least six months. Furthermore, the diagnosis differentiates between those who merely have fantasies or urges and those who act on them (APA, 2023).

In terms of presentation, individuals with this Disorder may appear secretive or overly private about their habits. They might develop patterns where they frequent specific locations or use particular tactics to observe others without getting caught. Some may also collect souvenirs or mementos from their voyeuristic acts. It is essential to approach this condition with understanding and care, recognizing that a complex interplay of psychological factors drives the behavior (Balon, 2017).

Diagnostic Criteria

Voyeuristic Disorder, as classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), is a paraphilic disorder focusing on observing unsuspecting individuals in intimate circumstances. To be diagnosed with Voyeuristic Disorder, an individual must meet specific criteria set by the DSM-5-TR.

- The individual experiences recurrent and intense sexual arousal from observing an unsuspecting person who is naked, disrobing, or engaging in sexual activities. This arousal is manifested by fantasies, urges, or behaviors (APA, 2023).

- The individual has acted on these urges with a non-consenting person, or these fantasies or urges have caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. This criterion emphasizes the harm or potential harm the behavior could bring to others or the distress it causes to the individual (Kafka, 2010).

- The individual is at least 18 years of age. This age criterion is important because it distinguishes between typical adolescent sexual curiosity and behavior that persists into adulthood. Adolescents may engage in voyeuristic behaviors out of curiosity, but it does not necessarily indicate the presence of a disorder (APA, 2023).

To understand the context of these criteria, it is essential to acknowledge that voyeurism is a relatively common behavior, especially in adolescence. However, for a diagnosis of Voyeuristic Disorder, the behavior must be recurrent and not just an isolated incident (Balon, 2017). Moreover, the distress or impairment caused by these urges or behaviors, or the acting on these urges with a non-consenting person, elevates voyeurism from a behavior to a disorder.

It is also worth noting that individuals with Voyeuristic Disorder may or may not recognize their actions' invasive and harmful nature. Some might justify their behaviors, while others might feel significant guilt and shame but find it challenging to control their urges (Balon, 2017).

The Impacts

Voyeuristic Disorder, as defined by the DSM-5-TR, has a range of impacts, affecting both the individuals diagnosed with the Disorder and those who are unsuspecting subjects of the voyeuristic behaviors. One of the most immediate impacts for individuals with the Disorder is the potential legal repercussions. Voyeurism is illegal in many jurisdictions and can lead to arrest, prosecution, and, in some cases, incarceration (Seto, 2008).

Apart from legal consequences, individuals with Voyeuristic Disorder may experience profound personal and interpersonal challenges. The recurring urges and behaviors associated with voyeurism can lead to significant distress, guilt, shame, and self-loathing (Kafka, 2010). The secretive nature of the behavior might lead to an isolating experience, with the affected individuals avoiding close relationships for fear of being discovered or due to the guilt associated with their actions (Balon, 2017). Pursuing voyeuristic opportunities can also hinder personal and professional growth, as the individual might prioritize these behaviors over other essential life activities.

The subjects of voyeuristic behaviors, often unsuspecting victims, can also face severe consequences. If they discover they have been observed without consent, they may experience feelings of violation, distress, and a decreased sense of personal safety. Such incidents can lead to long-term psychological impacts, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and a diminished sense of trust in others (McIvor & Petch, 2006).

Additionally, Voyeuristic Disorder can strain relationships, leading to mistrust and dissolution of partnerships or marriages. The stigmatization associated with the Disorder can further isolate individuals, limiting their access to appropriate therapeutic interventions or support groups. In the broader societal context, the prevalence of voyeuristic behaviors, both clinical and subclinical, can contribute to environments where personal privacy is undervalued and compromised (Seto, 2008).

The Etiology (Origins and Causes)

The etiology of Voyeuristic Disorder, like many psychological disorders, is multifaceted and not fully understood. Several theories and factors have been proposed, encompassing biological, psychological, and sociocultural dimensions.

From a biological perspective, some researchers suggest that atypical sexual preferences, such as voyeurism, might be associated with irregular brain structure or function, particularly in regions related to sexual arousal and impulse control (Cantor et al., 2008). Additionally, hormonal imbalances or irregularities might play a role in the development of the Disorder, as testosterone, in particular, has been linked to sexual drive and behaviors.

Psychologically, early sexual experiences and conditioning can contribute to developing voyeuristic tendencies. For instance, an individual might have had unintentional experiences of witnessing sexual acts during childhood or adolescence, and these incidents could have been paired with sexual arousal, reinforcing voyeuristic behaviors (Janssen, 2011). Childhood traumas or experiences of sexual abuse might also be contributing factors in some cases. Furthermore, cognitive distortions, such as justifying voyeuristic behaviors as harmless or believing that the observed individuals might be 'enjoying' being watched, can reinforce and sustain the behavior.

From a sociocultural standpoint, the influence of media and technology, especially the proliferation of easily accessible explicit content on the internet, might indirectly contribute to voyeuristic behaviors. While consuming explicit content does not directly equate to Voyeuristic Disorder, early and frequent exposure can desensitize individuals to the boundaries of privacy and normalize non-consensual observation (Derenne & Beresin, 2008).

In combination, it is likely that a confluence of these factors—biological predispositions, early life experiences, psychological factors, and sociocultural influences—interact in complex ways to contribute to developing and maintaining Voyeuristic Disorder. However, it is crucial to recognize that the precise etiological pathways can vary significantly between individuals, and not everyone exposed to the factors mentioned earlier will develop the Disorder.

Comorbidities

Voyeuristic Disorder, like other paraphilic disorders, can coexist with other psychological conditions, a phenomenon known as comorbidity. Comorbidities can provide insight into the broader psychological profile of individuals with Voyeuristic Disorder, their potential vulnerabilities, and areas of concern.

- Other Paraphilic Disorders: It is not uncommon for individuals with one paraphilic Disorder to exhibit symptoms or tendencies associated with another. For example, those with Voyeuristic Disorder may also show signs of Exhibitionistic Disorder, where there is a recurrent urge to expose one's genitals to an unsuspecting person, or Frotteuristic Disorder, characterized by a desire to touch or rub against a non-consenting individual (APA, 2023).

- Substance Use Disorders: Individuals with Voyeuristic Disorder may be more likely develop substance use disorders. Substance use can serve as a means of coping with guilt, shame, or anxiety associated with voyeuristic behaviors, or the substances might disinhibit an individual, leading to increased engagement in the behavior (Kafka & Prentky, 1994).

- Mood Disorders: Conditions like depression and Bipolar Disorder may coexist with Voyeuristic Disorder. The distress and potential isolation resulting from voyeuristic behaviors can contribute to depressive symptoms. Conversely, the manic phases of bipolar Disorder might exacerbate voyeuristic tendencies due to increased impulsivity and risk-taking behaviors (Abdo, 2016).

- Anxiety Disorders: The secretive nature of voyeurism, potential legal consequences, and societal disapproval can lead to heightened anxiety. Individuals might develop generalized anxiety, panic, or social anxiety disorders (McIvor & Petch, 2006).

- Personality Disorders: There can be an overlap between certain personality disorders and Voyeuristic Disorder. For instance, individuals with antisocial personality disorder might display a disregard for the rights of others, which can manifest in behaviors such as voyeurism. Similarly, those with borderline or narcissistic personality disorders might engage in voyeuristic behaviors as part of a broader pattern of impulsivity or need for validation (Black, 2015).

In clinical settings, recognizing these comorbidities is vital. Addressing only the voyeuristic behavior without attending to coexisting conditions might not yield holistic therapeutic outcomes. Moreover, understanding comorbidities can help devise more effective, individualized treatment plans.

Risk Factors

Voyeuristic Disorder, like many psychiatric conditions, has a complex etiology, with multiple risk factors contributing to its development. While no single factor guarantees the manifestation of the Disorder, several have been highlighted in the literature as potential contributors.

Early Sexual Experiences: Exposure to sexually explicit situations in youth can lay the groundwork for abnormal associations with sexual arousal. For instance, a child who repeatedly sees adults engaged in sexual activity might develop an association between secrecy, observation, and arousal. This covert observation can become a conditioned source of sexual pleasure, potentially setting the stage for voyeuristic behaviors in adulthood. Over time, the reinforcement of pleasure derived from such actions can solidify these tendencies, making them more challenging to address later (O'Donohue et al., 2000).

Childhood Maltreatment: Traumatic experiences during formative years can significantly impact an individual's emotional and psychological development. Such traumas can skew perceptions of what constitutes intimacy and consent. For some, voyeurism may emerge as a "safe" way to experience sexuality, free from the vulnerabilities associated with direct interpersonal interaction. In contrast, for others, it might stem from a distorted sense of boundaries and entitlement rooted in past traumas (Fagan et al., 2002).

Sexual Preoccupation: A heightened sexual drive or fixation can manifest in a spectrum of behaviors, not just voyeurism. When combined with other risk factors, such as early sexual experiences or cognitive distortions, an intense preoccupation with sex can amplify the drive to seek gratification through voyeuristic behaviors, making it a cyclical pattern that is hard to break (Kafka, 2010).

Social Incompetence: Individuals struggling with social interactions may find voyeurism appealing as it eliminates the need for mutual consent, intimacy, or the nuances of interpersonal communication. Over time, these individuals may favor voyeuristic behaviors over genuine human connections, further exacerbating their social inadequacies (Langstrom & Seto, 2006).

Cognitive Distortions: Maladaptive thought patterns can play a significant role in sustaining voyeuristic behaviors. Such cognitive biases might lead individuals to believe that their actions are harmless or even welcomed by the observed party. Over time, these justifications become entrenched, making it more challenging to recognize and address the problematic nature of their behaviors (Abel et al., 1985).

Neurobiological Factors: Emerging research in the neurobiology of paraphilias suggests that brain structures and hormone levels might play a role in these disorders. Abnormalities related to impulse control, decision-making, and arousal may predispose individuals to seek unconventional sexual gratification, such as voyeurism. However, this area requires further research to draw definitive conclusions (Cantor et al., 2008).

Coexisting Mental Health Conditions: Conditions like impulse control disorders, bipolar Disorder, or certain personality disorders might increase the inclination towards voyeuristic behaviors. The impulsivity or disregard for societal norms associated with some of these conditions can augment the propensity for voyeurism (Black, 2015).

Sociocultural Environment: Societal values and norms are vital in shaping individual behaviors. In cultures or settings where consent is not highly valued or where people are frequently objectified, voyeuristic behaviors might be more prevalent. Additionally, the rise of technology, which facilitates covert observation, combined with the ubiquity of explicit content, can desensitize individuals and normalize voyeuristic tendencies (Derenne & Beresin, 2008).

It is essential to understand that these risk factors can interact in various ways, and their presence does not guarantee the development of Voyeuristic Disorder. Instead, they highlight potential vulnerabilities that, in combination, might increase the likelihood of the Disorder manifesting.

Case Study

Background: Nathan, a 38-year-old male, presented to the clinic with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and shame surrounding his behaviors. He was single, worked as an IT consultant, and mostly kept to himself. Although he had a few close friends, he struggled with forming romantic relationships and often felt socially awkward.

Presenting Issue: Over the past six years, Nathan had developed a routine of secretly observing his female neighbors through their windows during the evening hours. Watching these women undress or engage in intimate activities had become his primary source of sexual gratification. Though he recognized his actions as inappropriate, he rationalized them, believing that if these women did not want to be watched, they would close their curtains.

History: Growing up, Nathan had inadvertently walked in on his older sister and her boyfriend several times. These unintentional observations became sources of arousal, and he sought similar opportunities to watch unknowing individuals as he matured. As a teen, he experienced bullying and was often sidelined in social situations, leading to feelings of social incompetence. This furthered his inclination to find gratification from observation rather than direct interaction.

Assessment: Upon assessment, it was clear that Nathan met the diagnostic criteria for Voyeuristic Disorder. His recurring and intense sexual fantasies and behaviors involving observing an unsuspecting person and the distress and impairment in his social functioning confirmed the diagnosis. There were also elements of cognitive distortions in the way he justified his actions.

Treatment Plan: Nathan's treatment plan consisted of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address his maladaptive behaviors and underlying cognitive distortions. Through CBT, Nathan was taught to recognize and challenge his unhealthy thought patterns and find healthier outlets for his sexual desires.

Given his history of social isolation and feelings of inadequacy, social skills training, and group therapy were also incorporated to help Nathan improve his interpersonal effectiveness and reduce his reliance on voyeuristic behaviors for arousal.

Outcome: After several months of therapy, Nathan began to show a decrease in his voyeuristic tendencies. He expressed guilt and remorse for his past behaviors and proactively sought ways to make amends. With the support of group therapy, Nathan also started to build more genuine social connections, reducing the sense of isolation that had been a significant factor in his Disorder.

Recent Psychology Research Findings

Research into Voyeuristic Disorder continues to evolve, shedding light on its nuances and complexities. One recent area of interest has been the role of technology, particularly the internet and smartphones, in voyeuristic behaviors. A study by Jenkins and Maier (2019) highlighted the proliferation of non-consensual image-sharing websites and forums as modern venues for voyeuristic gratification. The study showed that these digital platforms have made voyeuristic tendencies more accessible and, for some, more tempting, emphasizing the need for updated diagnostic criteria to encompass online behaviors.

Neurological factors have also been a focus in recent research. A 2020 study by Huang and colleagues investigated the neural substrates of voyeurism using Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans. fMRI measures the small changes in blood flow that occur with brain activity. It may be used to examine which brain parts handle critical functions, evaluate the effects of stroke or another disease, or guide brain treatment. They discovered that individuals exhibiting voyeuristic tendencies had heightened activity in the amygdala, a brain region associated with emotional processing and arousal when exposed to certain stimuli. This finding potentially points to a neurobiological basis for voyeuristic arousal (Huang et al., 2020).

Furthermore, researchers have been keen to understand the relationship between voyeurism and other paraphilic disorders. A comprehensive review by Lopes and colleagues (2021) highlighted significant comorbidity between voyeuristic Disorder and exhibitionistic Disorder, suggesting that these disorders may share common underlying etiological factors.

Lastly, therapeutic interventions for Voyeuristic Disorder have been a pivotal area of research. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) remains a primary mode of treatment, but a study by Fischer and Smith (2021) introduced a novel approach that integrates mindfulness-based practices. The preliminary results suggested that combining mindfulness with traditional CBT could reduce voyeuristic urges by increasing self-awareness and impulse control.

Treatment and Interventions

Voyeuristic Disorder, like other paraphilic disorders, often requires a tailored therapeutic approach to address its underlying causes and manifestations effectively. One of the mainstay treatments for this Disorder has been Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT). According to a study by Hanson and Morton-Bourgon (2005), CBT has effectively reduced recidivism among individuals with paraphilic disorders. In CBT, individuals learn to identify and challenge the distorted beliefs and thought patterns that fuel their voyeuristic tendencies while also developing skills to manage their impulses. This approach integrates cognitive restructuring and behavioral interventions, such as aversion therapy, to reduce the arousal associated with voyeuristic fantasies and behaviors.

There has been a growing interest in integrating mindfulness-based interventions into the treatment regimen in recent years. Fischer and Smith (2021) conducted research that combined mindfulness practices with traditional CBT for individuals with Voyeuristic Disorder. Their findings indicated that this combination was particularly effective, as mindfulness practices promoted greater self-awareness, helping individuals recognize and control voyeuristic urges before they escalated.

Pharmacotherapy is another avenue explored in the management of this Disorder. Some individuals benefit from medications that reduce overall sexual arousal or suppress specific urges, especially when acting on these urges is risky. Bradford (2001) highlighted the utility of anti-androgens and SSRIs in managing hypersexuality and related paraphilic disorders. While these medications do not "cure" the Disorder, they can significantly reduce the intensity of the urges, making it easier for individuals to engage in therapeutic interventions.

Lastly, group therapy has emerged as a valuable therapeutic intervention. Being in a group setting allows individuals to receive support from peers facing similar challenges, facilitating mutual understanding and shared coping strategies. Krueger and Kaplan (2002) emphasized the importance of group dynamics in promoting accountability, fostering empathy, and challenging cognitive distortions related to voyeuristic behaviors.

Treatment of Voyeuristic Disorder often requires a combination of therapeutic interventions tailored to the individual's needs. As with many psychological conditions, early intervention and a comprehensive approach yield the best outcomes.

Implications if Untreated

Untreated Voyeuristic Disorder can negatively affect individuals and those around them. Primarily, the Disorder can escalate in severity, with increasing risks of the individual acting on their urges more frequently or in situations with higher potential consequences (Rice & Harris, 2002). As voyeuristic acts are invasive and violate privacy, they may lead to significant distress, harm, or trauma for the observed individuals.

Moreover, there is an elevated risk of legal consequences. Engaging in voyeuristic behaviors, especially those that involve non-consenting individuals, is illegal in many jurisdictions and can result in criminal charges, fines, or imprisonment (Laws & O'Donohue, 2008). Such legal entanglements can lead to other adverse outcomes, such as loss of employment, stigmatization, and strained interpersonal relationships.

Psychologically, untreated Voyeuristic Disorder can increase guilt, shame, and isolation (Marshall & Barbaree, 1990). Over time, this can exacerbate other mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, or substance use disorders. Furthermore, as voyeuristic behaviors often provide temporary relief from underlying emotional or psychological distress, the untreated Disorder might see an individual increasingly relying on these behaviors as a maladaptive coping mechanism (Kingston & Bradford, 2013).

Additionally, untreated voyeurism might mask or be concomitant with other paraphilic disorders or related conditions. These disorders can remain unrecognized and untreated without appropriate therapeutic intervention, leading to a broader range of maladaptive behaviors (Kafka, 2010).

It is imperative to address Voyeuristic Disorder promptly. Leaving it untreated perpetuates the distress and risks for the individual and imposes potential harm on unsuspecting individuals and the community.

Summary

Voyeuristic Disorder, with its deeply rooted psychological intricacies, presents considerable challenges in both diagnosis and management. Historically, voyeuristic behaviors were relegated to criminal or deviant activities, often leading to punitive rather than therapeutic approaches (Langstrom & Seto, 2006). However, with advancements in psychological research and an increased understanding of human sexuality, perspectives have shifted. Over the decades, there has been an evolution towards a more compassionate and inclusive viewpoint, recognizing the condition as a mental health disorder rather than merely a manifestation of moral shortcomings (Krueger & Kaplan, 2002).

The potential for relationship disruption is significant for those with Voyeuristic Disorder. Voyeuristic acts can erode trust and intimacy in personal relationships, often causing profound distress and isolation for the individual involved (Marshall & Marshall, 2007). This can compound the existing struggles with identity and self-confidence, leading individuals to question their worth, ability to maintain healthy relationships, and place in society (Derenne & Beresin, 2008).

Furthermore, the stigmatization and potential legal implications can be particularly damaging for their immediate impacts and the overarching identity crises they can trigger (Laws & O'Donohue, 2008). As our understanding deepens, it is paramount that clinical approaches continue to adapt, aiming for holistic treatments that address the behavioral manifestations and the profound psychological and emotional turmoil associated with Voyeuristic Disorder.

References

Abdo, C. H. (2016). Paraphilic disorders: A concise review. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(4), 286-290.

Abel, G. G., Becker, J. V., Cunningham-Rathner, J., Mittelman, M., & Rouleau, J. L. (1985). Multiple paraphilic diagnoses among sex offenders. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 13(2), 153-168.

Balon, R. (2017). Paraphilic disorders: The current concepts. Psychiatric Times, 34(5), 16-19.

Black, D. W. (2015). DSM-5 guidebook: The essential companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bradford, J. M. W. (2001). The neurobiology, neuropharmacology, and pharmacological treatment of the paraphilias and compulsive sexual behavior. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 46(1), 26-34.

Cantor, J. M., Kabani, N., Christensen, B. K., Zipursky, R. B., Barbaree, H. E., Dickey, R., ... & Blanchard, R. (2008). Cerebral white matter deficiencies in pedophilic men. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42(3), 167-183.

Derenne, J., & Beresin, E. V. (2008). Body image, media, and eating disorders. Academic Psychiatry, 32(3), 154-158.

Fagan, P. J., Wise, T. N., Schmidt, C. W., & Berlin, F. S. (2002). Pedophilia. JAMA, 288(19), 2458-2465.

Fischer, D. & Smith, J. P. (2021). Mindfulness and voyeuristic Disorder: A novel therapeutic approach. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 29-37.

Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1154-1163.

Huang, L., Zhao, S., Zhang, Q., & Yang, J. (2020). Exploring the neural correlates of voyeuristic tendencies: An fMRI study. Neuropsychologia, 138, 107-114.

Janssen, E. (2011). Sexual arousal in men: A review and conceptual analysis. Hormones and Behavior, 59(5), 708-716.

Jenkins, W. & Maier, S. L. (2019). Digital voyeurism: The role of the internet in modern voyeuristic tendencies. Journal of Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 22(3), 155-161.

Kafka, M. P. (2010). Hypersexual Disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377-400.

Kafka, M. P. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for paraphilia not otherwise specified. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 373-376.

Kafka, M. P. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for voyeuristic Disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 317-324.

Kafka, M. P., & Prentky, R. A. (1994). Preliminary observations of DSM-III-R Axis I comorbidity in men with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 55(11), 481-487.

Kingston, D. A., & Bradford, J. M. (2013). Hypersexuality and recidivism among sexual offenders. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(1-2), 91-105.

Krueger, R. B., & Kaplan, M. S. (2002). Behavioral and psychopharmacological treatment of the paraphilic and hypersexual disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 8(1), 21-32.

Langstrom, N., & Seto, M. C. (2006). Exhibitionistic and voyeuristic behavior in a Swedish national population survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(4), 427-435.

Laws, D. R., & O'Donohue, W. T. (Eds.). (2008). Sexual deviance: Theory, assessment, and treatment. Guilford Press.

Lopes, G., Pereira, F., & Silva, C. M. (2021). Voyeuristic and exhibitionistic disorders: A comparative review. Journal of Sex Research, 58(1), 45-54.

Marshall, W. L., & Barbaree, H. E. (1990). An integrated theory of the etiology of sexual offending. In W. L. Marshall, D. R. Laws, & H. E. Barbaree (Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault: Issues, theories, and treatment of the offender (pp. 257-275). Plenum Press.

Marshall, W. L., & Marshall, L. E. (2007). The utility of the random controlled trial for evaluating sexual offender treatment: The gold standard or an inappropriate strategy?. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 19(2), 175-191.

McIvor, R. J., & Petch, E. (2006). Stalking and social anxiety. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 17(1), 86-99.

O'Donohue, W., Regev, L. G., & Hagstrom, A. (2000). Problems with the DSM-IV diagnosis of pedophilia. Sexual Abuse, 12(2), 95-105.

Rice, M. E., & Harris, G. T. (2002). Men who molest their sexually immature daughters: Is a special explanation required?. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(2), 329-339.

Seto, M. C. (2008). Pedophilia and sexual offending against children: Theory, assessment, and intervention. American Psychological Association.